Kodak. Blockbuster. Nokia. Motorola. BlackBerry. Xerox. AOL. Or how about RadioShack, Circuit City, or even Borders?

What do all of these companies have in common? All of them once were high-flying enterprises, household names with seemingly infinite prospects of continued growth. Kodak literally owned photography. Blockbuster owned home entertainment. Nokia, Motorola and BlackBerry owned the mobile phone and smart phone markets. Xerox invented the first PC. AOL owned email.

How did these companies lose their way?

And with all the gadgets and electronic gizmos that we all use each and every day, how did RadioShack and Circuit City manage to go out of business? And Borders? Okay, so Amazon happened. But people still read lots of books and listen to endless hours of audiobooks. With almost 20,000 employees and more than 500 stores in the U.S., wasn’t there a way to not only save the business but position it to thrive?

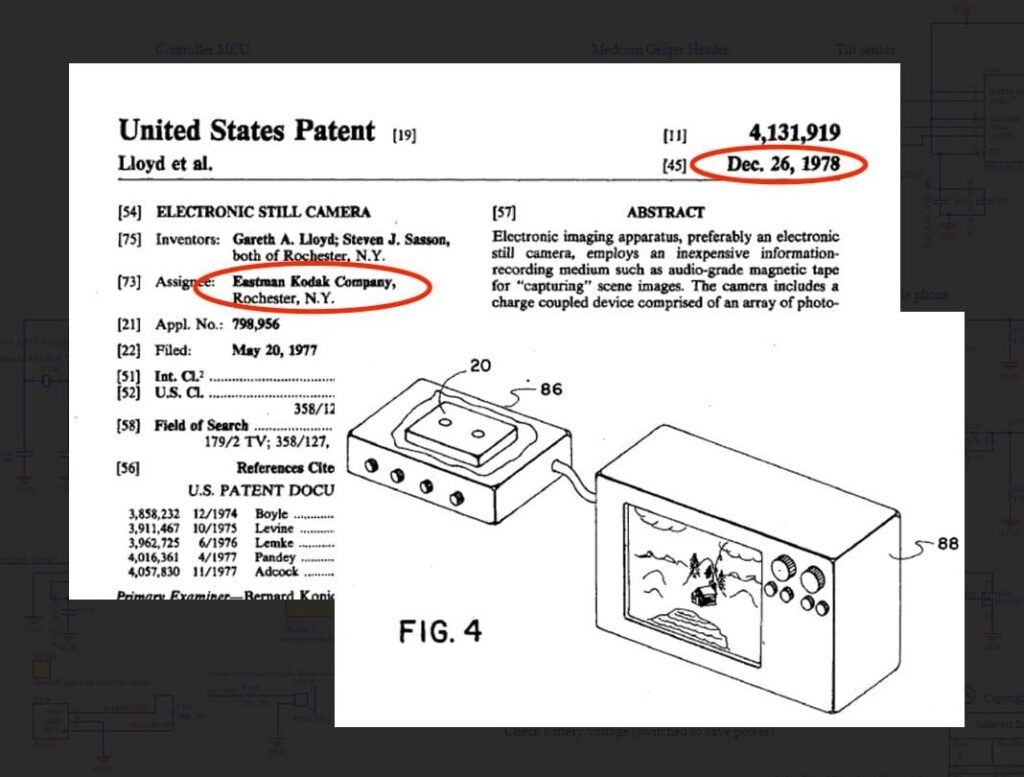

The same question could be, and should be, asked by shareholders of these companies. It all boils down to business transformation strategy. A company’s top management is paid to see around corners, to anticipate disruptive technologies and innovative new business models. How did Kodak get blindsided by digital photography? After all, they literally invented it and received the first patent for an “electronic” camera in 1978.

So what happened?

The common themes seem to be a mixture of complacency and an unwillingness or inability by the company’s board of directors to challenge management and hold the CEO accountable to plan for the unexpected. To plan for business transformation.

Even at well run companies there is an inherent information asymmetry between the board and the management team. No independent director spends 12-14 hours a day “living” inside a company’s balance sheet or profit and loss forecast — nor should they. As a result, a good chief financial officer will always know more about the intricacies of the company’s financial position than even a highly-competent audit committee chair. CEOs decide what information is presented to the board and then it’s up to directors to ask questions, demand more information, and to challenge management’s assumptions. Sometimes management is so close to the business that, as the saying goes, they can’t see the forest through the trees.

That’s where great boards really shine: to help management see the big picture and trends, rather than being consumed by day-to-day details.

When you have the right people around the table, representing diverse points of view, broad experiences from different industries and geographies, and you combine that with a boardroom culture that discourages “groupthink” while encouraging constructive and well-informed debate, that is a powerful combination.

Truth be told, after Kodak developed the world’s first digital camera for consumer use, the company was concerned that its launch would eat into its film business. So it decided not to put it on the market. According to industry estimates in the year 2000 a total of 85 billion photos were taken all around the world by people like you and me, mostly using traditional cameras and film. Kodak had such a prominent place in society that important personal milestones that demanded being recorded for posterity were called “Kodak Moments,” a company tagline. Use of digital photography since than has skyrocketed with an estimated one trillion photos taken in 2018 alone. Kodak declared bankruptcy in 2012.

Other companies have had near misses in terms of strategy. Microsoft almost missed the Internet revolution and it took an epic company-wide manifesto written by founder Bill Gates in 1995 to right the ship. Facebook nearly missed mobile computing in 2011 until Mark Zuckerberg announced that mobile platform development had to become priority number one.

Some founders and CEOs are true visionaries that have the charisma and discipline to see around corners at potential dangers ahead while keeping their hand firmly on the wheel of day-to-day operations and near-term execution. But most are not. Over the long term, value is created most consistently and effectively when shareholders pay a great deal of attention to who serves on a company’s board and how involved that board is in strategy development.

It is easy to get caught up in the Kodak Moment of the latest product launch, beating quarterly guidance on Wall Street, or opening a new headquarters. Great publicity and living inside the company’s public relations echo chamber can be exciting and even intoxicating.

But your company and its board of directors must stay focused on the long term, continue to challenge its own assumptions, innovate and operate an effective business transformation strategy.